Volunteers Growing Hope for Oysters in New Hampshire May 2013 Journal

Great Bay, an inland estuary in New Hampshire, provides crucial habitat for many plants and animals, including oysters. Great Bay contains North America’s northernmost intact oyster reefs. Records show that as many as 900 acres of oysters lived in the bay as recently as 1970; currently fewer than 100 acres remain. Disease decimated the oysters in the 1990s.

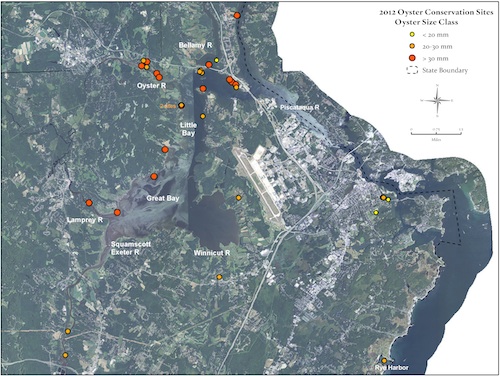

2012 Oyster Conservation Sites, Great Basin and Piscataqua River, New Hampshire |

Great Bay Estuary is in severe decline as a result of increased polluted runoff, especially higher nitrogen loads. The polluted runoff is largely caused by increased development occurring in the 52 communities within the 1,000-square-mile watershed that drains to the estuary.

The good news is that oysters can help clean the water by filtering out pollution. One oyster can filter as much as 20 gallons of water a day. To help restore Great Bay and improve its water quality, the Nature Conservancy coordinates the Oyster Conservationist Program, a partnership of several groups. The University of New Hampshire grows the baby oysters, or spat, at the University of New Hampshire Jackson Lab, and The Nature Conservancy trains volunteers and helps them grow oysters. In addition, the Coastal Conservation Association collects shells from local restaurants for the spat to grow on.

The local residents participating in the Oyster Conservationist Program have raised 50,000 oysters for restoration since the program began seven years ago. In 2012, 39 families helped grow baby oysters for restoration projects in Great Bay.

Each summer, oyster conservationists each receive a cage full of shells with the spat on them and host the babies in cages suspended from their docks until they are big enough to be moved to a Great Bay restoration site in the fall. Volunteers monitor their cages weekly to clean fouling from the cages and to pluck out predators, like green crabs, to help keep the oysters alive. They also measure the growth of the oysters biweekly.

Elizabeth Dudley, volunteer, and Kara McKeton, oyster conservationist coordinator with The Nature Conservancy, measure baby oysters, or spat, being raised by Dudley in a cage off of her dock. The oysters will help filter Great Bay’s water. Credit: Cathy Coletti, New Hampshire Coastal Program; August 2012 |

Since 2000, oysters have been making a slow comeback with the help of the Oyster Conservationist Program and other restoration partners, like the New Hampshire

Coastal Program, and approximately 15 acres of oyster reef have been restored to Great Bay. The pace of recovery is increasing, with an additional 5 acres of restoration planned this year.

However, disease still threatens the oysters, shortening their lifespan to only four to five years. Although their lifespan is limited, the restored oysters are still able to filter pollutants from the water, which improves water quality and helps other fish habitat like eelgrass. This summer the Oyster Conservationists will continue the project and grow hope for the future of oysters in New Hampshire.

To find out more about the Oyster Conservationist

Program, visit www.oysters.unh.edu/oyster_conservationists.html