Profile: Marnie Reed Crowell

Waxing poetic on the spring melt, lichens and all things natural

By Lori Valigra

Nothing tickles Marnie Reed Crowell’s imagination like

the spring melt. At the first signs of cracking ice, birds returning

from their winter retreats and buds clustering on branches, images

flood her mind and poetry runs through her fingertips onto paper.

The biologist-cum-poet and environment conservationist says every

season has its charms, but she loves melt. “I like to watch

new sprouts come up and the old, dirty snow melt away,” she

said excitedly. “And then I like to see which things are

on time. It’s a bit of detective work.” Some birds always

return on time, triggered by daylight. “Increasing day is

a metaphor for optimism,” said Crowell.

Crowell, a Deer Isle, Maine, resident originally from New Jersey,

doesn’t see the line often drawn between science and artistic

expression. The daughter of an entomologist, she grew up fascinated

with the natural world. She fell in love with both words and science,

and to this day still hasn’t chosen between them. And like

her father, she possesses a natural curiosity about the things

she doesn’t know in nature, and an unstoppable willingness

to share what she does know with anyone within earshot. “I

grew up explaining how an entomologist was insects and

an etymologist was words,” she said. “My father

taught me the scientific and the common name for everything we

saw. I had a hard time choosing between arts and science.”

Ultimately, she didn’t choose, but wove the two together,

teaching high school biology and Latin. Crowell has since published

a number of books on natural history as well as poetry. “I

called my first book Greener Pastures because I thought

any pasture is worth greening,” she said. Perhaps some of

the inspiration for that book came from teaching biology to inner-city

sophomores in Camden, New Jersey, who didn’t spend much time

getting to know the natural world around them. “As far as

they were concerned, a little brown bird was a kind of bird. That

was a bird species.” Crowell, a Deer Isle, Maine, resident originally from New Jersey,

doesn’t see the line often drawn between science and artistic

expression. The daughter of an entomologist, she grew up fascinated

with the natural world. She fell in love with both words and science,

and to this day still hasn’t chosen between them. And like

her father, she possesses a natural curiosity about the things

she doesn’t know in nature, and an unstoppable willingness

to share what she does know with anyone within earshot. “I

grew up explaining how an entomologist was insects and

an etymologist was words,” she said. “My father

taught me the scientific and the common name for everything we

saw. I had a hard time choosing between arts and science.”

Ultimately, she didn’t choose, but wove the two together,

teaching high school biology and Latin. Crowell has since published

a number of books on natural history as well as poetry. “I

called my first book Greener Pastures because I thought

any pasture is worth greening,” she said. Perhaps some of

the inspiration for that book came from teaching biology to inner-city

sophomores in Camden, New Jersey, who didn’t spend much time

getting to know the natural world around them. “As far as

they were concerned, a little brown bird was a kind of bird. That

was a bird species.”

Wild times in the city

Crowell believes anyone can sensitize themselves to nature, starting

with small steps. For example, city dwellers could notice the

subtler signs of spring’s onset by seeing the discoloration

at the bottom of a tree. If they’re inquisitive, they might

look beyond what most would call “scum” and consult

a guide book at their local library. In the book they’d discover

they had seen one of the two or so lichens that can survive city

air pollution. Country dwellers may be able to identify 30 species

of lichens on trees where the air is purer, she said. But merely

noticing that there is something growing on the tree is a step

closer to nature. “You may not be able to name them [the

lichens], but you’re a step ahead of yesterday when you didn’t

know they were there,” she effused. “So the world just

keeps getting richer and richer.”

|

|

|

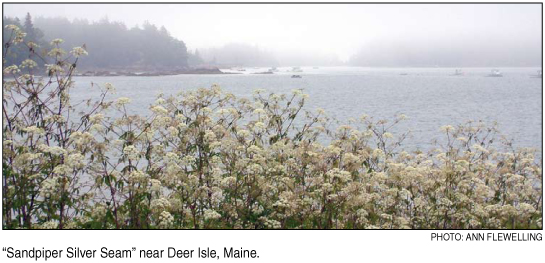

Nowadays, Crowell, keen-eyed and energetic at 69, explores

Deer Isle, where she puts her astute and sensitive observations

and interactions with nature into verse that even the most science-challenged

can understand. Working at her side much of the time is photographer

Ann Flewelling, who brings the dimension of physical imagery to

the stanzas of her poems. The two call their verbal/visual collaboration

“threehalf press,” because the combination of one plus

one person can be more than two. Their most recent book, Beads

& String: A Maine Island Pilgrimage, is a collaboration

that highlights Deer Isle’s preserves. New chapters focused

on months of the year appear each month on the Web site of Island Heritage Trust, a conservation

land trust for Deer Isle, Stonington and the surrounding islands.

Proceeds for the book, to be published in full in the spring,

will go to the Trust.

A trust emerges

The volunteer-run Island Heritage Trust is another of Crowell’s

loves. She and her husband, Ken, an ecologist, were instrumental

in its origins in 1987. It was Ken’s work studying the mouse

populations on different islands surrounding Deer Isle that helped

enlarge the circle of people interested in donating land or easements

to maintain the pristine character of Deer Isle. Crowell said

it’s not necessary to be a Rockefeller to donate land or

services, such as the proceeds of a book, to a land trust. “No

one was a millionaire on Deer Isle,” she said. She and Ken

met many islanders through Ken’s work. They also volunteered

to give nature walks and talks, which inspired other islanders

who attended to donate land or easements to the Trust.

Their interest in conservation began in New Jersey, where both

are from, and where they got involved in The Nature Conservancy,

which later led to their work in the land trust. Of Deer Isle’s

24,000 acres (9,712 hectares), so far 2-3 percent are preserved.

Hear Marie read her poem "Dowsing" click to play click to play

Crowell, her husband and their Deer Isle friends started the

land trust. What is amazing about Deer Isle, Crowell said, is

that almost all of the preserves in the early years were gifts

from people. “Nobody was wealthy. Emily Muir had to sell

some of her land so she could afford to give away that other land,”

said Crowell of local builder, architect and artist Muir, who

decided to give the backland where she was building a line of

houses along a cove as a nature preserve.

Crowell admitted those were good years, but now people considering

making donations have a tougher decision with the rapid escalation

of land prices. “Land preservation is entering a new phase,”

she said. “How do you deal when you’re now talking millions

of dollars? The last couple of years the preserves have been purchased,

not given. People may be generous, but they’re not going

to give away a million-dollar nest egg.”

But there are smaller, still important contributions that can

be made. “Most of my contribution has been I donated my talent,”

she said. ”It happens we came to Deer Isle early on, so we

were able to acquire 30 acres (12 hectares) of land that’s

right next to a preserve. We gave the conservation easement on

it.”

But Crowell feels her more significant contribution to the

land trust has been reaching the local people through nature walks

and books, work that inspired the people who owned properties

to find a good mechanism to donate. “That’s totally

satisfying,” she said.

Artists as educators

So what is the artist’s role in preserving the environment?

“An editor at Reader’s Digest told me the key

to success is that people want to know what it’s like to

be inside someone else’s skin. So I’ll tell you what

it’s like to be me and go mackerel fishing.” Crowell

doesn’t think artists are obligated to have an environmental

cause or bend to their work, but she does suggest to her artist

friends that making an artist’s statement could be useful.

Crowell said most of the local artists do make such a statement,

for example, Carolyn Caldwell. “Why do I paint?” she

says in her artist’s statement on her Web site. “Vanishing beauty. The world

is changing rapidly. Development is overtaking the natural world….My

hope is that artists can slow the rush.”

Said Crowell, “She could have painted ugly stuff, but

she chose to paint beautiful stuff and serenity and say, ‘look,

if we don’t take care of it, this is what we’re going

to lose.’”

It’s not just professional painters, photographers or

writers who can speak for the environment. Crowell admits she

wasn’t trained to write. She felt compelled to do so. She

also hails the advent of new technologies like digital cameras,

which make it easy for people to capture and share images via

home-made newsletters, the Internet and other ways.

Hear Marie read her poem "Spotted Sandpiper" click to play click to play

“If you’re a city person looking at ants and then

go to the museum and look at the display, how do you share that?

Do you share it in your local co-op newsletter? Do you share it

in your school newspaper? You probably can find someplace to share

it, and it probably will mean something to other people,”

she said. “Part of what I do, by the way Dowsing and

other poems, is for people who spend their life’s energy

in a city working hard. They need their battery recharged,”

she added. “So by reading Dowsing they’ll feel

better, like holding hands with wind on the bay.”

Crowell recommends carrying around a small notebook, or jotting

creative thoughts, phrases and inspirations on them. “I had

to learn to trust my own flash of emotion or inspiration,”

she said. “What I see in the natural world is usually a metaphor

that has a deeper meaning to me. It is a highly spiritual experience,

like Dowsing or Mackerel. Both of those poems are

pretty humbling. Like Dowsing. I literally was walking

around the Isle with a stick in my hand and Ann looked at me and

said you’re doing a poem aren’t you? And I said I suppose

I am. What is the poem about? It’s about holding these sticks

in your hand. Formerly bayberry, these are ordinary twigs, but

I like the way they feel in my hand. I’m half expecting them

to pull down toward the center of the earth like a dowser. And

then I realize this is so interesting it must be the way a lobster

feels in communion with something bigger and since it’s sea

you’d call it Neptune or Poseidon.” Crowell recommends carrying around a small notebook, or jotting

creative thoughts, phrases and inspirations on them. “I had

to learn to trust my own flash of emotion or inspiration,”

she said. “What I see in the natural world is usually a metaphor

that has a deeper meaning to me. It is a highly spiritual experience,

like Dowsing or Mackerel. Both of those poems are

pretty humbling. Like Dowsing. I literally was walking

around the Isle with a stick in my hand and Ann looked at me and

said you’re doing a poem aren’t you? And I said I suppose

I am. What is the poem about? It’s about holding these sticks

in your hand. Formerly bayberry, these are ordinary twigs, but

I like the way they feel in my hand. I’m half expecting them

to pull down toward the center of the earth like a dowser. And

then I realize this is so interesting it must be the way a lobster

feels in communion with something bigger and since it’s sea

you’d call it Neptune or Poseidon.”

She added, “What I would encourage everybody to do is

when you get those thoughts, work on them, play with them, make

them more exact and meaningful. Words have an abstract melody.

Listen to that. You don’t need to go to a poetry class. Allow

yourself to listen to it as an abstract sound. And the pattern

of words that most fit, play with that for a week or so and look

at it again. A better way of arranging it will occur to you. That

tinkering is what’s making poems.”

Lori Valigra is editor of the Gulf of Maine Times.

For more of Marnie Reed Crowell’s and Ann Flewelling’s

work visit: http://www.threehalfpress.com.

|